New battle before Iran and Syria to revive trade

Syria is Iran's strategic partner when it comes to political and security cooperation, but not only their economic and commercial cooperation does not correspond with the realities of their ties, but it has also decreased in recent years.

Before the 2011 conflict, Iran’s presence in the Syrian market was not limited to the export of non-oil and oil products, where Iranian technical and engineering services companies and some industrial firms had an active involvement in the country’s projects.

Between 2007 and 2017, Iranian companies implemented various technical and engineering projects and investments worth about $2.5 billion, but they ground to a halt after the war started.

Other Iranian investments in Syrian industries such as the automotive sector almost stopped or sharply declined for similar reasons.

As guns fall silent and the Syrian government re-establishes central control over much of the country, the wider confrontation is shifting to a new battleground: the economy.

There is already a shift among countries to improve relations with Damascus, no less by the states that once supported militants fighting to topple the Syrian government.

Damascus has made clear that it has no interest in Western support for reconstruction in view of the West’s role in the war and the fact that its help will be tied to unacceptable political demands.

The government concentrates instead on securing investment and assistance from “friendly countries” that stood by Damascus during the conflict, naturally putting Iran in pole position.

Last week, Syrian Minister of Foreign Affairs Faisal Moqdad, Minister of Economy Samer al-Khalil and Minister of Communications and Technology Iyad al-Khatib visited Iran along with a group of senior managers and experts to attend a meeting of the joint economic commission of the two countries.

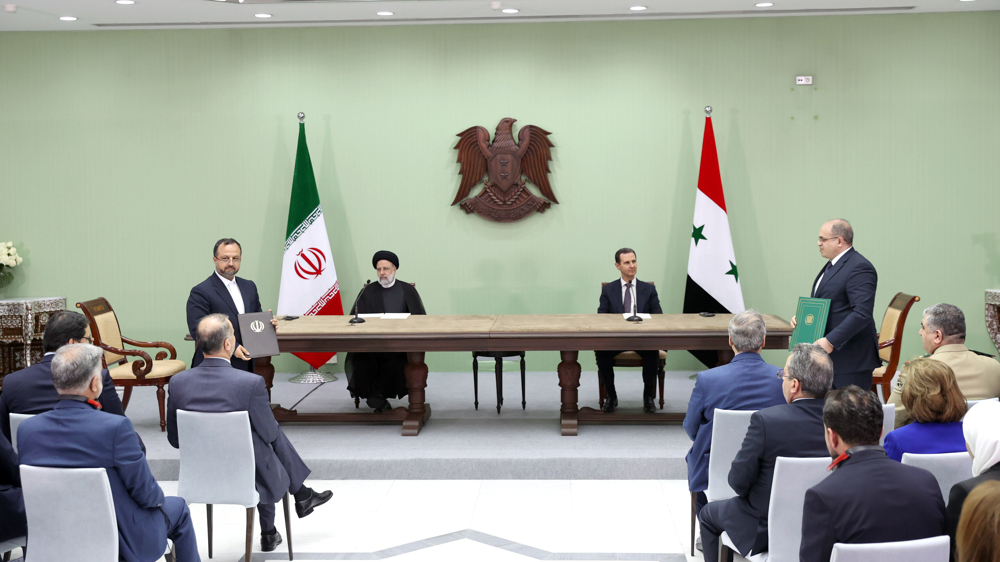

The get-together aimed to follow up on the implementation of the cooperation documents signed during President Ebrahim Raeisi’s visit to Syria in May and the agreement reached to work out strategic plans.

The two-day visit, the first by an Iranian president to Syria since 2010, had culminated in the signing of 15 “cooperation documents” that would allow “both countries to open a new chapter in economic relations”.

Syria has suitable economic and commercial capacities in agriculture, industry and minerals. It produces wheat, barley, cotton, lentils, peas, olives, beets, beef, mutton, eggs, chicken, and milk.

It also assembles cars and produces oil, textiles, food, beverages, tobacco, phosphorite and cement. The country’s mineral resources include oil, phosphate, chrome, manganese ore, asphalt, iron ore, salt, marble, gypsum and hydro.

The war and Western-led sanctions have had a devastating effect on Syria’s economy. In 2008, Syria’s overall foreign trade stood at $30 billion. In 2020, this figure was barely at $5 billion.

Meanwhile, the post-conflict economic trajectory is interesting.

According to International Trade Center (ITC) statistics for 2020, Turkey accounted for 38.5% of exports worth $1.6 billion to Syria, China 20% with $834 million, Egypt 7% with $289 million, Russia 4.4% with $183 million, India 3% with $124 million followed by Lebanon with $122 million.

Iran’s exports to Syria stood at about $120 million, giving it a no better rank than seventh in the Syrian market. According to unofficial reports, a part of Iran’s exports to Iraq and the UAE is re-exported to Syria.

Tehran and Damascus are working to raise their bilateral trade to a target of $2 billion by 2025. To achieve this, they are moving towards free trade, having signed a raft of agreements on taxation, customs, transportation, standards and quality maintenance.

In 2009, they signed a free trade agreement, but it was implemented only for 88 items exchanged between the two countries, according to one official, who said restrictions imposed due to the economic issues of the two countries practically limited the use of the deal for traders.

Problems related to bank exchanges and transfer of money are another detractor, while the transport of goods by sea, in the absence of a tripartite agreement with Iraq for land transportation, is time consuming and costly.

Moreover, the war and the resulting insecurity plus sanctions have led to the partial closure of domestic and international economic and commercial communications and activities in Syria.

They have sharply cut state revenues and led to a decline in the value of the national currency and the purchasing power of consumers and the migration of many businessmen.

Hence, the country is not an easy terrain for trade.

Nevertheless, the strategic political partnership formed during the difficult years of war makes many observers believe that the two countries would be ready to go to any length to revive trade and forge stronger economic relations.

Iran and Syria previously agreed to establish a joint bank and insurance firm during President Raeisi’s visit to Damascus, aimed at further facilitating direct bilateral trade.

During the recent visit of the Syrian delegation to Tehran, they reached a landmark agreement on a zero-trade tariff deal, signaling a significant step in enhancing economic cooperation between the two countries.

An Iranian bank is set to start operations in Syria within the coming weeks, Iranian Minister of Roads and Urban Development Mehrdad Bazrpash said, adding that it was a significant achievement considering the typically prolonged process involved.

“Normally, such endeavors would take several years, so obtaining permission for the Iranian bank to operate in Syria within three months is worth appreciating,” Bazrpash said during a meeting with al-Khalil, the Syrian minister of economy.

What they have now to do is to create infrastructure for direct land and sea transportation of goods and establish stability and security in Syria.

They also need to support and facilitate business communication between their private sectors and coordinate between government and private institutions.

Studies show there is a market in Syria for at least $700 million worth of non-oil Iranian goods on top of $600 million in exports of technical and engineering services a year.